Dr. Albert Twers: A Life for Humanity

Origins in Bukovina – An Ideal on the Brink

Albert Twers was born on December 13, 1904, in Rădăuți, a town in the Habsburg crown land of Bukovina. This region is often romanticized as the home of "Homo Bukovinensis" – an ideal of the supranational European who saw cultural synthesis rather than threat in a web of languages, religions, and ethnicities. Yet, this myth carried a dark underside.

The Jewish poet Rose Ausländer, a contemporary of Twers, described the falling silent of this world with the words: "They were silent in five languages." She thus precisely named the moment when idealized multilingualism became a mask and neighbors fell silent as political systems collapsed. Albert Twers grew up in this multifaceted world. His family was ethnically Czech and lived a multi-confessional normalcy – Catholic and Protestant roots existed side by side without conflict, but also without the privileges of the ruling classes. His father Hermann, originally a trained locksmith, fell seriously ill and had to retrain as a tailor under great hardship to support the family. When he died in 1909, five-year-old Albert was left nearly destitute with his mother Ida.

Education Against All Odds – The Influence of Naftali Alpern

Albert's childhood was marked by material deprivation but also by an unwavering intellectual determination. He attended the renowned "Eudoxiu-Hormuzachi" Gymnasium in Rădăuți, a bastion of humanistic education. Since his mother could not support him financially in any way, Albert financed his entire school and later university years completely by himself through private tutoring given to younger students. This ability to convey knowledge in a structured manner and maintain moral rigor was inherited from a man who would shape his life: Naftali Alpern.

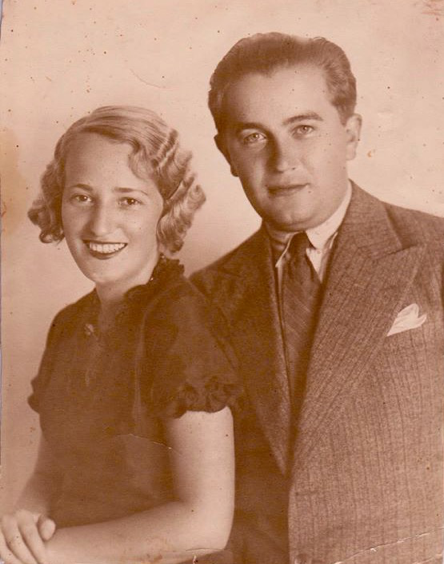

Alpern was a classical philologist who had studied Greek and Latin in Vienna. His humanistic thinking and intellectual integrity became a moral compass for Albert – long before history demanded radical courage from him. Through Alpern, he met his daughter Deborah, whom he married in 1933. Her liturgical name was Musia, but in everyday life, she was Deborah. The connection to this Jewish-bourgeois family opened the doors to Jewish culture and piety for Albert. For him, having grown up in multi-confessional normalcy, this transition was not a "conversion" in the religious sense, but a cultural and emotional merging of two worlds, free from ideological weight.

Military Service and Rise – The Perversion of Loyalty

After his military service, which he completed in 1925 as a non-commissioned officer of the reserve in the Romanian army, Albert began studying law in Chernivtsi. He graduated in 1928 and was admitted to the bar as a lawyer in 1931. It is crucial to highlight his military time: it established his relationship with the state and duty. Albert served the Romanian state loyally – the same institution that would later persecute him as "unreliable," then as "politically suspicious" due to his marriage, and finally as an "ethnic German" (Volksdeutscher).

While he was building his career, Romania became fascist. The Iron Guard gained influence, and antisemitism was elevated to state doctrine. As early as 1938, the Jewish population was subject to systematic exclusion.

1940: The "Russian Year" and the Paradox of Flight

In June 1940, the global situation of Bukovina changed abruptly. The Soviet Union occupied Northern Bukovina. Rădăuți remained Romanian but was overwhelmed by a massive stream of refugees. The so-called "Russian Year" (1940–1941) awakened traumatic memories among the population of the Russian occupations during the First World War. People vividly remembered the indiscriminate taking of civilian hostages, the deportations to Siberia, and the deep-seated antisemitism of the Russian army.

This led to a historical paradox: although the Romanian fascists were already openly propagating murderous hatred, thousands of Jews fled from the north to the Romanian south. The fear of Soviet arbitrariness, expropriation, and Stalinist terror weighed heavier than the fear of local antisemites. Many of these refugees, as well as locals like Albert, saw joining the Romanian army or professing loyalty to the state as a way to prove their allegiance to the Romanian royal house – in the desperate hope that monarchical tradition would protect them from destruction.

1941: Transnistria – The Topography of Death

In the summer of 1941, following the invasion of the Soviet Union, violence escalated in the Romanian sector. It was primarily Romanian troops and the local gendarmerie who acted with brutal force in Rădăuți. Executions, robberies, and violent assaults by parts of the civilian population occurred immediately. Deportations to Transnistria began in the late summer of 1941. This area was not a camp in the classic sense, but a vast, barely administered death zone. Here, people did not die in gas chambers, but through calculated starvation, cold, typhus, and arbitrary killings. The number of victims cannot be exactly recorded but is estimated to be in the range of several hundred thousand people. Among the deportees was Deborah's entire family – her parents and three brothers. Albert achieved the impossible: through his brother, who held a significant position at the military court in Iași and had access to Marshal Antonescu, he obtained a repatriation permit. A nearly unique occurrence that brought the entire Alpern family back to Rădăuți.

The Voluntary Path into Hell – The Courier of Hope

After his own family was safe, Albert could have remained silent. Instead, he voluntarily returned to Transnistria as a courier. His work was a matter of extreme logistical hardship under constant threat to his life. He was the only link between the deportees, who legally no longer existed, and the outside world. He smuggled: 192 letters: This collection is today an archive of pain and hope.

They contained signs of life and pleas for help. Essential goods: He brought medicine, candles, and clothing. Tools for dignity: He transported chemicals for tanning, simple dental instruments, fabric scraps, and sewing materials. This enabled the people in the camps to maintain a minimal livelihood and a remnant of self-respect through manual labor.

Arrest and the Destruction of Civil Existence

At the Chernivtsi railway station, Albert was finally arrested. The Romanian secret police searched for an espionage charge, found none, and instead constructed a case for "circumventing censorship." The trial was political theater. As a lawyer, Albert knew the law, but he faced a system that had long since wielded the law as a weapon against humanity. His license to practice law was revoked, his assets were confiscated, and his professional existence was destroyed. The conviction was an attempt to destroy the moral authority of a man who had acted against state cruelty.

The Soviet Perversion: From Savior to Gulag Prisoner

After the collapse of the Antonescu regime in 1944, no justice followed. The Soviet occupying power did not see him as a lifesaver but arbitrarily classified him as an "ethnic German" based on his name and biography. The Jewish community of Rădăuți – people who had survived the war only through his courage – wrote an impressive letter to the Soviet authorities. They testified that he was Czech, spoke Yiddish, and had actively saved hundreds of people from death. That a Jewish community in a Stalinist state dared to write such a letter is a historical event in itself. But the Soviets ignored it. Albert was sentenced to forced labor in a Soviet Gulag and deported to a copper mine. For three years, he survived under inhumane conditions.

Request by the Radauti religious community to the NKVD Albert Twers not to be pursued

An End in Quiet Dignity

When he returned, he was barely recognizable. Under the communist regime in Romania, he was never allowed to work as a lawyer again. He was demoted to a simple worker in a sawmill. Yet he remained a man of quiet dignity. He spoke little, never complained, and preserved his humanity in a world that did not reward it. Albert Twers died in 1972 in his hometown of Rădăuți.

Legacy

His life stands for the decision to do what is right, even when the state forbids it. He stands for the fact that civil courage is a form of love for people, not for systems. Dr. Albert Twers proved that the dignity of the individual can be stronger than the violence of any dictatorship.